Most people get the theory of SEO: You find the keywords and phrases that compose the search queries of your target audience, and you build content that answers the questions implicit in those queries. But a lot of marketers I talk to are skeptical about how to do it. They did the keyword research. They built the content. And they still can’t get ranked. What’s wrong with SEO?

There’s nothing wrong with SEO. But the theory as described is an oversimplification. Google doesn’t rank anything based solely on how well the semantics of the piece relate to the query. Your content can be indexed by Google for the keywords it contains. But it is not likely to rank for competitive terms unless your site demonstrates authority on the topic.

Domain authority is not a new concept, it’s been a staple of good SEO for a long time. For example, I wrote the following in 2010:

PageRank is designed to ensure that the most relevant, authoritative sites are listed at the top of search results. The primary way that a site gains authority is by publishing insightful, accurate, or definitive information in a compelling way, so that other people will want to link to it. (Audience, Relevance, and Search: Targeting Web Audiences With Relevant Content, p. 114)

In the book, I said that the aim of a site which has identified the topics of interest to the target audience is to become a hub of authority on those topics. Doing that means not just building one piece of content about the topics, but building the depth and breadth that are the hallmarks of authority. It helps when you link to other authorities on the topics. And it helps even more when other authorities link to you. But there’s no shortcut to gaining authority on a topic. You have to develop a lot of content, and it needs to be interwoven into experiences for the target audience.

The problem with the earlier SEO theory is it presents SEO as a shortcut to traffic. There are no shortcuts. Some things have gotten easier since 2010. For example, the Penguin algorithm has discredited millions of low-quality external links, placing a premium on internal links in the process. Because you control internal links, you can become a hub of authority mostly by creating a large body of content. Other things have gotten more difficult. For example, the Panda algorithm helps Google identify low-quality pages, raising the bar for content quality across the whole body of content.

But the basic concept is the same: Don’t just answer the primary question implicit in the query. Answer all the questions in all the related queries. In the book I said you should be the Wikipedia of your most important topics. This was not a popular statement among marketers, who want to tell stories and preach brand value. I don’t think the three things are mutually exclusive. But nobody reads your stories or gets your brand value if you don’t become a hub of authority on what your stories or your brands are about.

Limiting keyword tracking undercuts success

I’ve run SEO for the largest private publisher on the web. At that scale, one of he biggest challenges is duplicate content. In my zeal to govern content across the enterprise, I probably went overboard on cutting apparent duplicates. I have cut a lot of pages that might not get a lot of traffic by themselves, but serve to provide the breath of coverage we needed to support the main topics of interest to our target audiences. I didn’t realize how much of mistake this was until recently.

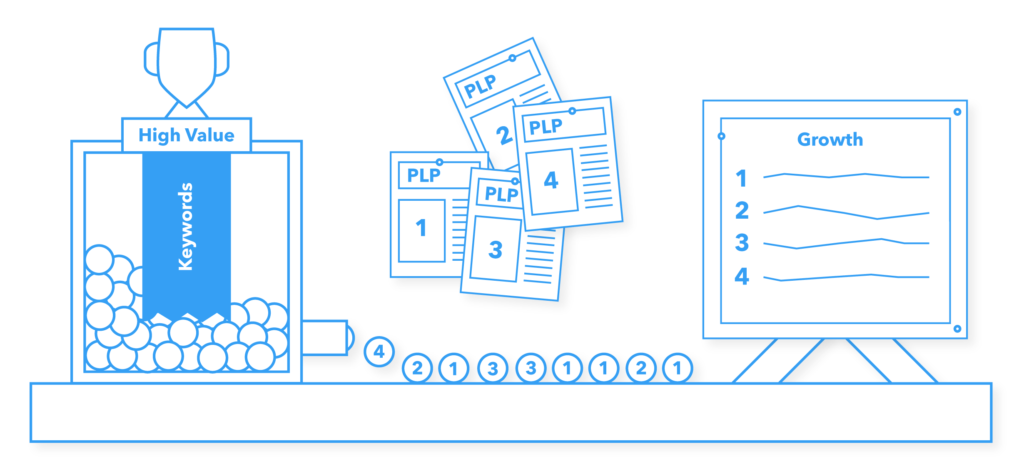

The main way we govern keywords (which represent topics of interest) across an enterprise is by assigning preferred landing pages (PLPs) to them. Some SEO tools effectively limit the number of keywords you can assign and track by charging by the keyword. So enterprises typically track progress month over month against a limited number of PLP/keyword assignments in terms of ranking, bounce rates, engagement rates, etc. This is what most SEO tools do.

The problem with the practice is it does not go far enough in identifying how these PLPs fit into an ecosystem of pages on related topics from all over the web, especially internally. You can see how you rank, but you don’t have a complete picture of how the related pages about relevant keywords lend support to a page through their links. With modern SEO tools, your small keyword footprint limits your ability to track related long-tail keywords and their pages. These are the pages that need to link to your high-value pages, to lend them enough authority to rank.

This is why many marketers are skeptical of the way SEO is practiced today. By focusing only on the high-value keywords, and assigning individual PLPs to those keywords, you are ignoring the thing that influences ranking the most. As an SEO, you report to your stakeholders monthly that your ranking has not improved significantly (again), but the tools say very little about how to change that.

You especially can’t see what gaps in your current site need to be filled with fresh new content, the kind that could lend support of your PLPs if you had it. So you spend most of your time trying to fix load times or JavaScript or other technical issues, because those are the only things that actually move the ranking needle. You never get to the stuff that is the promise of my book Audience, Relevance , and Search: using search engines as a proxy for audience intent.

A better way: keyword knowledge graphs

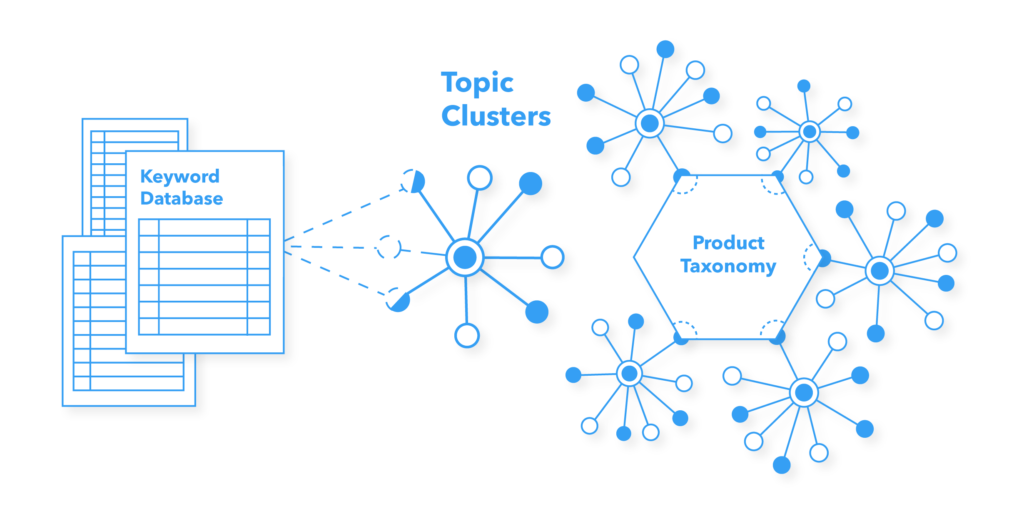

I have published a lot of content on keyword knowledge graphs on this site. In an article I referred to them as keyword ontologies. In a Webinar hosted by Mike Moran, I called them keyword knowledge graphs. The concept is the same. You develop a database of relevant keywords that cluster into topics, and you relate those clusters to your product taxonomy. This is how you can develop an inclusive database of all the keywords your clients and prospects are interested in, and how their content needs can be filled in a systematic way.

Doing this at scale is arduous, and requires some pretty rare AI firepower. I’m pretty lucky to have some of that firepower on my Marketing AI team. Most companies are not so lucky.

Fortunately, there is a company that can do this for you. MarketMuse has technology that can build you a keyword knowledge graph with lots of content and linking recommendations for any of the topics of interest for your audience. It can even suggest what those topics are for a given product category.

The company has stayed true to the idea that to rank for competitive topics, and you have to become a hub of authority for those topics. Unless you already have a lot of content stashed away in developer forums or product documentation, this typically involves creating dozens of pieces by authorities and other influential authors on those topics, then linking them together into coherent client journeys.

I had the chance to meet up with MarketMuse co-founder Jeff Coyle at a recent conference. He said the message suggested by the data is often hard for marketers to hear. They don’t have teams of strong writers and editors to create the needed content at scale. They lack the people to take the insights and put them into practice.

But the business case is easy to write. If you become a hub of authority on the topics of interest for your target buyers, you can tell them stories and otherwise influence a high percentage of them to move to purchase. If you don’t become a hub of authority, you have to buy eyeballs, clicks, and leads. If you took half of your paid media budget and invested it in building high-end content teams–with the right content planning, authoring, and optimizing software–you can double the leads and triple the wins for the same money.

Conclusion

When it comes to providing the content your target audiences need at scale, there are no short cuts. You need deep AI to understand how to become a hub of authority on their topics of interest. And you need to develop a strong marketing editorial department that delivers the content that meets audience needs at all stages of their client journeys. The sooner you accept this truth, the sooner you can get off the paid media merry go round and start developing a strong client base.